Scheme for PCB dumps spurs outcry

GE proposes three landfills for southern Berkshires

By DAVID SCRIBNER

Contributing writer

PITTSFIELD, Mass.

On its 100-mile journey to Long Island Sound, the Housatonic River etches a winding path south from Pittsfield to Lenox Dale, in a sequence of oxbows twisting through a lush floodplain on the floor of a valley between the Berkshire Hills.

It is a river revered for its scenery and for the diversity of wildlife it supports. Woods Pond in Lenox Dale and Rising Pond in Housatonic, each created by paper mill dams across the river, are favorite haunts for canoeists and kayakers.

But appearances can be deceiving. The Housatonic is also a river contaminated, down to its floodplain bedrock, with polychlorinated biphenyls, a class of chemicals the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency declared in 1976 to be a probable carcinogen. From Pittsfield to Sheffield, signs posted by the state Department of Environmental Protection along the river warn that the water is neither suitable for swimming nor the fish safe for consumption. Among the highest concentration of PCBs ever recorded in waterfowl have been discovered in ducks that have lived along the Housatonic River.

Now environmental officials are weighing how best to clean up the meandering river – and whether to sign on to a proposal to create three landfills in southern Berkshire County for PCB spoils that might be dredged from the river.

Like the Hudson River to the west, the Housatonic’s contamination came from a General Electric factory. For 40 years, GE’s sprawling transformer construction and repair complex in Pittsfield allowed PCB-saturated insulating oil, estimated in the millions of pounds, to seep into the river, where the compound drifted south, binding itself to sediment, and becoming impounded in high concentrations in the bottom of Rising and Woods ponds.

After a five-year project in which GE spent hundreds of millions of dollars to scour PCB pollution from its urban property and a two mile-long section of the river in Pittsfield, the EPA is now turning its attention to what it calls “the rest of the river.”

The federal agency, joined by its counterparts in Massachusetts and Connecticut, has ordered General Electric to come up with a comprehensive plan, termed a “corrective measures study,” to remove PCBs from the largely rural, meandering riverbed from Pittsfield’s Canoe Meadows to Great Barrington, about 20 miles.

Last month, GE submitted a 1,200-page proposal for what the company deemed an appropriate cleanup. The EPA has extended to 60 days the public comment period on the GE document, and it will begin reviewing the company’s strategy early next year.

GE’s proposal

The company is proposing a “monitored natural recovery,” a concept that relies upon natural dispersal rather than extensive dredging to remove PCBs. But in some areas, such as Woods and Rising ponds, where PCBs have collected in large concentrations, GE has proposed removing or confining the contamination – and building three landfills for PCB-laden sludge.

That concept may sound familiar to some in the Hudson Valley of New York, where a public outcry over PCB landfills proposed in the 1980s effectively delayed any cleanup of the river for nearly two decades. The Hudson PCB cleanup finally got started last year, but only after the EPA required that the toxic sediment removed from the river would be shipped out of the area by rail to an approved landfill in Texas.

For the Housatonic, however, GE rejected the use of the rail line that runs along the river to cart away dried sediment dredged from the river. Instead, the company envisions three potential local dumps – “upland disposal facilities” — in Lenox, Lee and the village of Housatonic, keeping the toxic material in the community from which it was dredged.

Such a method became highly controversial in Pittsfield. To the dismay of local residents there, sediment scraped from the river was relocated to giant mounded landfills adjacent to an elementary school.

The concept is even less popular in the southern Berkshires, as a crowd of local residents and public officials made clear last month at an information session in Lenox hosted by Ian A. Bowles, the state’s secretary of energy and environmental affairs.

In the neighboring town of Lee, GE has identified a 193-acre parcel on Forest Street as the location for a landfill to contain 1 million cubic yards of PCB sediment. The site is just below Goose Pond, one of the Berkshires’ purest lakes, and along Goose Pond Creek, which descends to the Housatonic River.

“We have worked for 20 years to enhance our town, to make it appealing to visitors,” declared Lee Selectman Pat Carlino. “We don’t want people getting off Exit 2 of the Mass Pike to see a PCB dump. We will fight it.”

In Housatonic, a village within the town of Great Barrington, GE quietly purchased a 106-acre parcel along the western edge of Rising Pond, between the river and the Housatonic Railroad line. GE’s report says 84 acres of that property could potentially be used as a PCB landfill containing 2.9 million cubic yards of contaminated material.

“Is there any way we can stop this?” Great Barrington Town Planner Christopher Rembold wondered aloud.

‘Worst kind of cleanup’

GE’s strategy has divided the environmental community, just as it did a quarter-century ago along the upper Hudson, and some suspect it was intended to do so here.

“Everything that GE is doing with its proposal is designed to scare people into imagining the worst kind of cleanup,” said Mickey Friedman of Great Barrington, a longtime environmental activist and member of the Housatonic River Initiative. “GE knows there are environmentally sensitive ways to remove PCBs. But there is a billion dollars at stake for GE. They are not to be believed. PCBs are terribly toxic. Only a careful and complete cleanup will keep wildlife and people safe.”

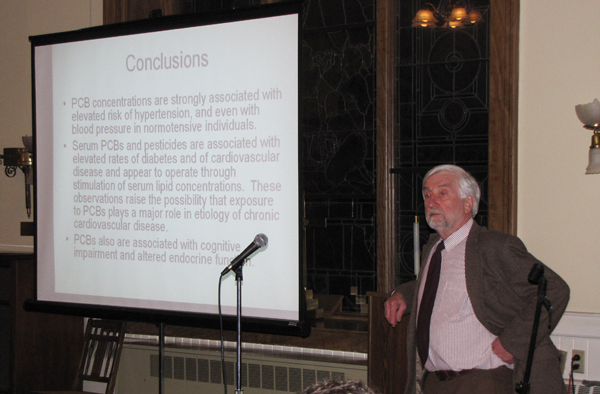

Friedman cites the research of David Carpenter, a neurotoxicologist at State University of New York at Albany, whose research concludes that because PCBs tend to volatilize, those people living near toxic waste sites are likely to suffer higher rates of disease.

Shep Evans of Stockbridge, a member of the Berkshire Land Trust, argued that the cost of not removing the PCBs would go far beyond the price of cleaning up the river. The cleanup cost is estimated to be in the millions if not hundreds of millions of dollars, depending on how thoroughly the EPA decides the river must be cleansed.

“It will take a huge amount of time, political anguish and sacrifice by everyone to clean up a mess that should never have been made in the first place,” Evans told environmental officials at last month’s forum. “But removal of contaminated soil is a public works project, and we know how to do that. The restoration is doable, and we should remember that the river changes all the time. It is its own architect, and after it’s cleaned up, it will re-establish its own course. But it will be clean – and far better, because we won’t be condemning future generations to living with a contaminated river that they can’t use.”

Even so, the prospect of wrecking the ecology and habitat of the Housatonic River in the short term for the sake of cleaning it up – with an invasive program of dredging — is anathema to Berkshire sportsmen.

“We need an environmentally sensitive approach,” said Mark Jester of Lenox, president of the Berkshire County League of Sportsmen’s Clubs.

Tim Gray, founder of the environmental watchdog group Housatonic River Initiative, said such a minimally invasive procedure might be available if the EPA and GE were willing to adopt it.

“There is a company in California that has successfully decontaminated a PCB toxic waste site by introducing a bacteria that breaks the compound down,” Gray explained. “This method met the requirements of the California Department of Environmental Protection. This bacteria occurs naturally, but in its natural state it would take 10,000 years to remove all the PCBs from the Housatonic. But the California company has added a protein to the bacteria that makes it consume PCBs at a higher rate.”

He also pointed out that there is very precise dredging equipment that can remove polluted sediment with a minimum of damage to the environment.

But in general, Gray warned that “all landfills eventually fail, regardless of how well they are engineered to sequester the contamination.”

His group is urging the EPA to explore alternative methods of PCB removal, such as the bacteria. In December, the Housatonic River Initiative will host a forum on such alternative methods, with testimony from firms that have developed successful decontamination practices.

It will be a challenge to convince the EPA to adopt one of these newer cleanup methods, however.

“Innovative technology is hard to introduce into the EPA’s approach,” Gray said. “The EPA has to avoid legal challenges to their recommendations, challenges that would characterize their methods as arbitrary or capricious. So they go with dump and dredge, which they know.”

The advantage of groups such as the Housatonic River Initiative, he said, is that they can help to put a spotlight on the alternatives.

“The HRI wants to push the envelope on exploring cleanup strategies that will be minimally destructive to the environment,” he said. “We think there are new solutions that haven’t yet been given a thorough hearing.”

The above article appeared in the November 2010 issue of the Hill Country Observer.